This is the second installment of the two-part article by Syed Rizwan Zamir, which explores how Sayyid Ali Naqi Naqvi attempted to revive South Asian Shi’i Islam in the 20th century through the ethical and mytho-theological example of Imam Husayn. Here, we learn of Imam Husayn’s role in the sacred and eternal story of Islam, a sacrifice that transforms not just Muslims and their moral consciousness, but indeed, all of humanity. The first part of the article may be accessed here.

PART II: A MYTHO-THEOLOGICAL UNIVERSE

The discussion thus far makes clear that Sayyid Naqvi approaches both Husaynology and the broader Islamic sacred history with the same interpretive lens. Yet the parallels between Sayyid Naqvi’s Husaynology and his telling of Islam’s sacred story do not end with hermeneutical similarities; quite crucially, they extend to the narrative itself, where, narratively speaking, Imam Husayn becomes a crucial figure within Islam’s sacred history. This narrative intersection between Husaynology and Islam’s sacred history is crucial to understanding why Imam Husayn is ascribed the all-important role of “illuminating Islam” for Sayyid Naqvi’s contemporary Muslim and non-Muslim audience. Though not always made explicit, Husayn’s heroic act is situated within an underlying mytho-theological story of Islam. I will now turn to situating Karbala and Imam Husayn within the broader narrative of Sayyid Naqvi’s presentation of Islam’s sacred story.

The Mythical Backdrop

History of Islam (Tārīkh-i Islām) covers the historical terrain that begins from “the beginning,” and ends with the death of the Prophet. What is predominantly a work on the life of the Prophet opens with the creation story, under the section “Beginning of Creation” (Āghāz-i āfarīnash):

Allah and Allah alone was there, and nothing else. By the gesture of His Will was born a light that illumined the possibilities of existence within the all-pervasive darkness of non-existence. Thirteen other lights were radiating in that luminous arena. In the rays of these lights that became the encompassing atmosphere, millions of small and big lights began tossing and rolling about restlessly [for expression]. There was no temporality for us to tell how long this lasted. Then, spirits were born, who, along with the lights, swept the breeze of life for all that was other than God. All beings with spirits, which were to be born till the day of Resurrection, were now gathered with their qualities of will and intelligence. The Creator then took a pledge from them regarding the knowledge of, and obedience to their Lord. They affirmed and covenanted the same. (1, emphasis added)

This mytho-theological story continues until the jinns, angels, and eventually Adam appear on the scene (4). Despite God’s command, ʿAzāzīl—a jinn who was accepted into the company of angels in Sayyid Naqvi’s telling—refuses to prostrate to Adam, God’s representative on Earth. He was banished from the company of angels, but asked for permission to explore the fate of humans and possibly mock God’s claim of human superiority over angels. God responded: “You can strive your hardest but some sincere and virtuous humans will live such that they will not succumb to your instigations, and will not deviate from the path of truth and virtue.”(4)((Here Sayyid Naqvi is referring most probably to Qurʾan, al-Isrāʾ (17):64-65: “Rouse whichever of them you can with your voice, muster your cavalry and infantry against them, share their wealth and their children with them, and make promises to them—Satan promises them nothing but delusion—but you will have no authority over My [true] servants: Your Lord can take care of them well enough.”)) Humanity until today then is caught between upholding God’s covenant and the machinations of ʿAzāzīl, now Satan.

Eve is born as Adam’s mate, and together Adam and Eve inhabit the Garden. Eve was tempted by Satan, who in turn convinced Adam to taste the fruit of the forbidden tree. Adam and Eve were banished to Earth—where they had to reside anyway—and regretted and repented for their disobedience. Their repentance was accepted. Now it was their task to cultivate the Earth into a dwelling place through having progeny. God granted Adam knowledge of all that was necessary for sagacious living. Since marriage among brothers and sisters needed to be prohibited, houris descended from Heaven for that purpose. Seth became the successor of Adam’s mission on earth, while the story of Cain and Abel—the other two sons—is presented as the archetypal story of humanity caught between the forces of light and darkness. (5-6)

…[A] historical lens cannot really carry the burden of the subtleties of reality’s depth. The reality which is called “Islam” has always existed…

At this junction, Sayyid Naqvi makes a statement that is key to his discussion. He introduces Islam as the perennial religion in the following words:

The message Adam brought was indeed Islam; teachings given by Noah were also Islam. Similarly, all God-sent messengers and prophets were missionaries of Islam. From this perspective, the biographies of Adam, Noah, and other prophets are all part of the history of Islam. However, a historical lens cannot really carry the burden of the subtleties of reality’s depth. The reality which is called “Islam” has always existed, but it was not given the terminological name “Islam” [as yet]. We learn from the Glorious Qurʾan that the term Islam began from the time of the revered Abraham. As mentioned in the Qurʾanic verse, “Strive hard for God as is His due: He has chosen you and placed no hardship in your religion, the faith of your forefather Abraham. God has called you Muslims—both in the past and in this [message]—so that the Messenger can bear witness about you and so that you can bear witness about other people” (al-Ḥajj (22):78), he was the elderly sage who named the followers of this religion “Muslim”. The first ones to be named with this title were Abraham and his son Ishmael, and they prayed to God to keep this title alive for their progeny (al-Baqarah (2):127-128): “As Abraham and Ishmael built up the foundations of the House [they prayed], ‘Our Lord, accept [this] from us. You are the All-Hearing, the All-Knowing.128 Our Lord, make us surrender ourselves to You; make our descendants into a nation which surrenders itself to You. Show us how to worship and accept our repentance, for You are the Ever-Relenting, the Most Merciful.” It clarifies then that the progeny of Abraham that descended from Ishmael and followed the correct religion can be considered followers of the religion of Islam. It is because it is the religion of their great patriarch [i.e., Abraham], the perpetuation of which through his shared progeny with Ishmael they had prayed. Therefore, the religions of Judaism and Christianity that were established within the progeny of Isaac during the intervening [period] were unique to the Israelites; they were not for the children of Ishmael. The religion for the progeny of Ishmael was the same Abrahamic religion that was titled a “nation of ḥanīfīyyah” or Islam, and which according to the Qurʾan was a competitor to Judaism, Christianity and idolatry: (Qurʾan, Āl ʿImrān (3):67) “Abraham was neither a Jew nor a Christian. He was Muslim ḥanīf, never an idolater.” (7-8)

The next section is titled “Abraham the Friend of God and His Islamic [Heroic] Deeds (kārnāmay),” where Abraham is recounted heroically fighting three battles: 1) against idolatry; 2) against the worship of celestial objects, idols, and humans—i.e., worshipping Nimrod—; and 3) his personal sacrifice and willingness to die as the “first one offered to Islam.” (8-13) Given the special destiny of Abraham in the Divine plan, “In the end, He protected Abraham and his martyrdom did not occur.” (13) Yet these heroic deeds did not lead to faith for the community, and when all levels of arguments did not overcome unbelief, “The missionary of Islam chose emigration so that other parts of God’s Earth can be illuminated with the invitation to truth. There were only two people of faith who accompanied him: one his honored wife, Sarah, and the other his nephew, Lot.”((He cites Qurʾan, al-ʿAnkabūt (29):26 here: “Lot believed him, and said, ‘I will flee to my Lord: He is the Almighty, the All Wise.”)) Arriving in Syria from Babylon as “the first emigrants of Islam,” they settled in Palestine. Lot was called to preach to Jordan, but yet again, “The only answer his people gave was to say, ‘Expel Lot’s family from your town, for these are a people determined to be pure.’” (Qurʾan, al-Naml (27):56) And they were driven out: “These are the earlier traces (nuqūsh) of Islamic history that have turned events of affliction (maṣāʾib), pain (takālīf), torment [from others], homelessness, and exile, into the treasured beginnings of Islam.((As the reader may have noticed, this is the context for the quote cited earlier in this essay.)) While Lot’s community was punished, except for Lot’s wife, his family was saved: “His wife, who was exempt of qualities of faith and virtue was separated from him and met with divine punishment. A lesson to ponder, O people of insight.”((See Qurʾan, al-Ḥashr (59):2, a clear evidence again for Sayyid Naqvi’s underlying ethical aims for his historical pursuits.)) (15)

The story then takes a turn from battling the world to an inward family battle. With growing age and no children, Sarah herself suggests marriage with Hagar; yet with the birth of Ishmael—and Abraham’s natural affection for Hagar for that reason—Sarah wished both to be taken away from her presence.

Veiled behind [this family crisis], Divine wisdom saw an opportunity for a huge nation, a great country, nay, the establishment of a center for the worlds. That is why He appointed His friend [i.e., Abraham] to act upon Sarah’s insistence and take Hagar and their son outside Syria. [Imagine] the land of Palestine and that of Mecca. The guidance of the same Supreme Guide that had brought the friend [i.e., Abraham] this far, brought him to a place where there was no fountain, no greenery, no agriculture, where he left his wife, who trusted fully in God, and her suckling child without any ostensible means of support and returned to Syria (17).

At this stage, he recounts the legendary thirst of Ishmael and Hagar’s seven rounds of running between hillocks of Safa and Marwa in search of water, and the miraculous gushing of the stream of Zamzam. Echoing the same ethos of Islam that set the stage earlier, he sums up in a nutshell the deeper currents that define and make sense of the historical unfolding of Islam as the perennial religion:

This was the foundation of Islam’s center in whose account helplessness, exile, emigration, hunger, and thirst are clearly perceptible. The same intensity and pain would become the preamble for the happiness and prosperity (farrākhī wa khush ḥālī) that was to come. “So truly with hardship comes ease, so truly with hardship comes ease.”((Qurʾan, al-Sharḥ (94):6.)) (17)

The sole purpose of appointing prophets, messengers, and religious leaders is to offer its lofty illustrations [of sacrifice].

The next section recounts the well-known sacrifice of Ishmael. That the memory of this event was kept alive ritually and communally both in the pre-Muhammadan and Muhammadan eras are presented as confirmation of why it was Ishmael, and not Isaac—as the Jews and Christians claim. The episode is discussed at some length, and as usual various ethical and theological points are highlighted all along. For the purposes of this discussion, what’s most significant is the concluding passage((Why this passage is so significant should become clear in the ensuing pages.)):

“Thus, do We reward the virtuous”((Qurʾan, al-Ṣāffāt (37):106.)) is a proclamation of a general principle that our complete order [of creation] is linked through sacrifices; the right to rewards for accomplishing high ideals and for winning God’s pleasure is proportionate to the amount of sacrifice made. “That was indeed a conspicuous ordeal. And We ransomed him with a mighty sacrifice.”((Qurʾan, al-Ṣāffāt (37):107-8.)) In fact, all commandments, callings, and the entire code of religious conduct rest on demanding sacrifice from humanity. The sole purpose of appointing prophets, messengers, and religious leaders is to offer its lofty illustrations [of sacrifice]. If Ishmael’s sacrifice had been the supreme model of sacrifice before God, it would not have been postponed, nor would it need the substitution [of a lamb]. But because in the Divine knowledge the most perfect and complete sacrifice was yet to come from within Ishmael’s progeny (had Ishmael’s sacrifice assumed finality, the lineage that was [destined] to set in order the complete history of sacrifices would not have existed) in view of the “Greater Sacrifice” it was thought proper by the Creator to postpone Ishmael’s sacrifice through substitution. (21)

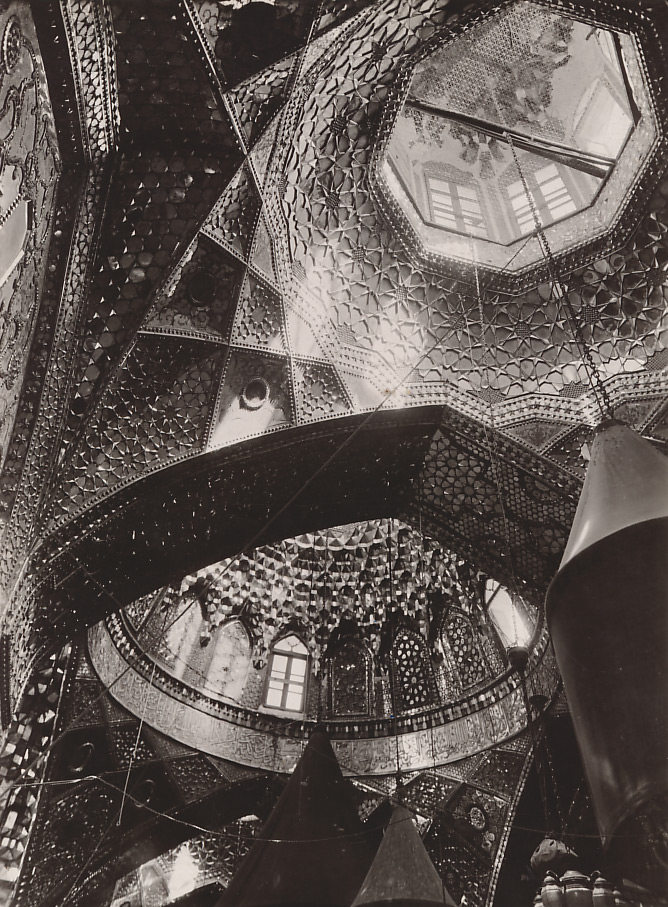

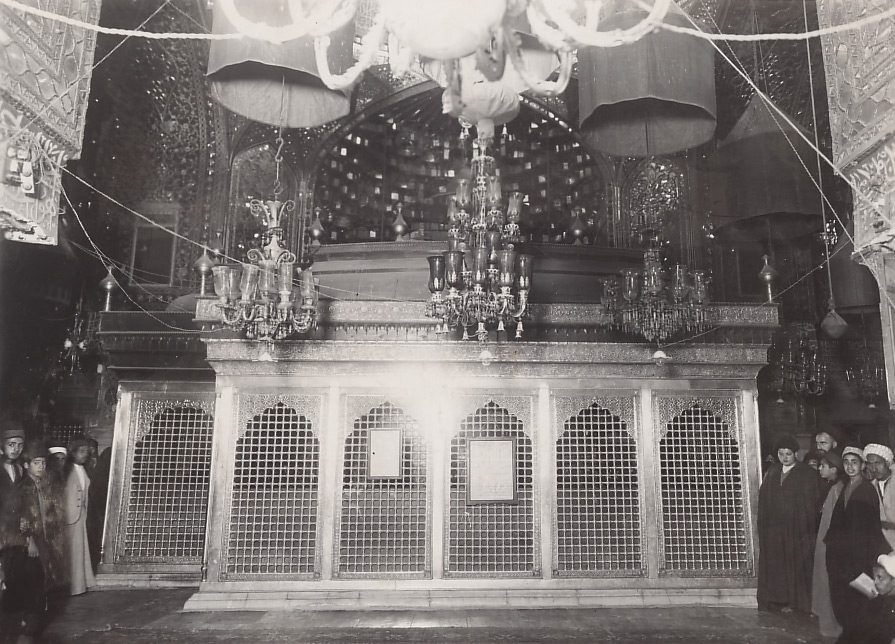

The ensuing section, “Construction of the Kaʿbah,” then discusses Abraham and Ishmael’s collaborative building of Islam’s Holy Temple. Citing the Qurʾanic passage, “the first House erected for people was the one at Bakka, a blessed spot and guidance for the worlds (hudan li-l-ʿālamīn),”((Qurʾan, Āl ʿImrān (3):96.)) Sayyid Naqvi notes that “to call ‘House’, a ‘guide for the worlds’ indicates the existence of some [beings] who are of this House (ahl al-bayt—the People of the House) who shall be the source of Divine mercy and guidance for the worlds. The most perfect among them was spoken to [by God in the following words]: ‘We sent you [O Muhammad] not, but as mercy to the worlds.’”((Qurʾan, al-Anbiyāʾ (21):107.)) (22)

God commands Abraham to invite people to the pilgrimage. Instituting the Hajj as his final act, Abraham leaves the scene for his progeny to carry his mission forward. Rewarding Abraham’s tireless strivings and special prayer (“Our Lord, I have settled some of my progeny in a valley where no vegetation grows, near your Sacred House, our Lord, that they may perform the prayers. Make people’s hearts turn toward them.”((Qurʾan, Ibrāhīm (14):37.))) God declares the Sacred House the center of pilgrimage for all, as a means to the end of turning “people’s heart toward Abraham’s progeny.” (23)

Beginning from page 24, Sayyid Naqvi traces the Prophet’s Ishmaelite lineage. In the process he underlines a special role for this lineage, “the guardianship of the Sacred House,” (34-5) and certain duties: to never accept an idle life; avoid discord within the community; and “to the furthest extent, be strivers on the path toward unity and accord.” (32-33) In tracing the lineage, only one historical event is narrated at length: the event of the Elephant. Abraha—the monarch of Yemen—built a cathedral which he sought to make the center for pilgrimage that will replace the Sacred House in Mecca, which he then sought to raze to the ground. When Abraha’s army detained his camels, ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib complained to Abraha. Abraha’s army mocked him for being worried about camels, when he should have been more worried about the Sacred House from which Quraysh drew all of its honor. ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib responded in the following words: “I was the owner of the camels, so I spoke about them; the House belongs to Someone Else who will protect it Himself.” (39) Asking all to move outside Mecca, ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, along with his chosen people spoke to God at the Sacred House: “Everyone must defend his house, so must You.” (39) Leaving the Sacred House in His Owner’s hands, ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib awaited the outcome. The Owner of the House intervened through miraculous feathered flocks, “hurling at the army stones from the hell-fire and left them like worm-eaten leaves.”((Qurʾan, al-Fīl (105).)) The event became legendary among the poets of Arabia who kept its memory alive. In one confrontation and opposition with Quraysh, ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib felt helpless and prayed for being gifted ten sons, and if heard, he pledged to sacrifice one. The prayer was heard, and he remembered the burdensome task of offering one of his sons as a sacrifice. Lots were cast and it turned out to be ʿAbd Allah, the father of Muhammad. People advised him to sacrifice camels instead. He kept casting lots with ten camels added to the offering, and only at a hundred was the burden lifted from him.

This mytho-theological prelude to the “history of Islam” told in the first 41 pages sets the stage for the coming of the Prophet of Islam and his prophetic career. Inevitably, the Prophet Muhammad is carrying forward—according to the Divine plan—the unique mission of his patriarch, Abraham. The next 500 pages are then the telling of Muhammad’s life till his departure from the world. Without this grand narrative within which is embedded all that Muhammad is supposed to perform in his role and function, his life and prophetic career would barely make sense. It was Muhammad’s inescapable burden to carry forward the special role and duties of his Ishmaelite lineage.

Is the History of Islam “Historical”? The Hermeneutical Circle of Mytho-Theology, History, and Ethics

So what kind of historian is Sayyid Naqvi, and what kind of history is he writing? The discussion thus far makes it clear that Sayyid Naqvi’s historical narrative is embedded within a mytho-theological universe, in other words, the mytho-theological universe of Shiʿi Islam. Since for Sayyid Naqvi—and the wider Muslim tradition as well—Islam is a perennial religion (in fact, the only religion according to the Qurʾan) an account of Islamic history could not begin with the Prophet of Islam in the 7th century, but with “the beginning”, the creation story. That is why early sections of the book trace Islamic history from creation to Adam, from Adam to Abraham, and then, Abraham through to the Prophet of Islam. Jewish and Christian prophets and revelations are, therefore, an integral part of this story. Although humans do make choices in history that have good or bad consequences, history is not independent of the Divine Plan. Recall Sayyid Naqvi’s observation that, “Divine wisdom saw an opportunity for a huge nation;” Abraham was needed to execute the Divine plan. History does not operate independent of the Divine Will, a clear indication of the mytho-theological universe that is driving the lens of history.

Just as the ethical is intertwined with the historical, the historical in turn is intertwined with the mytho-theological. History as “narration of what happened at a given moment in historical time” is thus embedded within a “sacred mythology” that sets the backdrop for the meaning of these events. Mytho-theology and history thus meet within an interpretive circle which makes it impossible to separate them, or point out a clear hierarchy between the two. Even when he seemed to be historicizing mythology—and ran into serious controversies—the historical analysis was an extension of this mytho-theology that undergirds the vision of history itself.

History does not operate independent of the Divine Will, a clear indication of the mytho-theological universe that is driving the lens of history.

But what is the meaning of history, of this sacred story? What is this story about? The answers are found right within Sayyid Naqvi’s writings and speeches on Husaynology and Islam’s sacred story; it is performed on almost every page. The meaning is the lessons learned from the story. Meaning is ethical. It is an ethical story, and that of an ethical human life. The mytho-theological, historical, and the ethical are clearly intertwined and united. Yet, this strong sense of the underlying unity of Islam’s historical narrative is a result, not of historical analysis itself, but the mytho-theological framework that sets its backdrop.

In the final analysis, the interpretive circle encompasses within it the ethical, historical, and the mythological. Though a rational and critical lens is brought to particular historical details all throughout, the exercise in history draws its own vision and raison d’etre from the mytho-theological, and is simultaneously guided—and restricted too—by the quest for the ethical. In sum, the intellectual enterprise of “history” as narration of “what happened” is informed by the mytho-theological story that makes history possible on the one hand, and on the other, by its intended goal: the ethical well-being of human beings and human societies. In support of this reading, Islām kī Ḥakīmānah Zindagī provides an even more elaborate comment:

In reality, if we are commanded to cry and mourn, and the best of rewards are reserved for it, it is because when we consider these rewards, then we will be willing to reflect on the [various] situations (ḥālāt), and it will impact our actions. If through [mourning this] calamity, the event was not given this importance, then like every other incident of history this event would have as well been limited to history books; that every child of ours knows this event would not have been possible. And we were not even familiar with it, how could we have gained any lesson from it? This calling [of Karbala]—from calamity to mourning and practical impact—necessitated by nature, was to institute this [practice] so that the event is not forgotten, the real benefits of the event are preserved and the real objective of the event is established (qāʾim rahay).((Interestingly, the words in italics appear in Shahīd-i Insānīyat, p. 584 as well.)) Even the minutest details of the incident of Karbala are exemplary in teaching Islam. Every action has a dimension of education in it. The incident of Karbala, despite its brevity in terms of time [in which it occurred], was the center of the core teachings of Islam. Teaching of every practical subject—from the rights of God (ḥuqūq Allāh), to the rights of [fellow] human beings (ḥuqūq al-nās), relating to the character-formation of a family (tarbīyat-i manzil), the criterion of governance and rule, culture, an individual or society’s life, with respect to the conditions of love; in sum, all moral, conceptual, and practical teachings—are contained within Karbala. That is why even the minute details of the incident carry such importance that they need to be conveyed to us… (Islam kī Ḥakīmānah Zindagī, 67-8, italics added)

Altogether then, the exercise in historical research is about preserving stories that are worth reflecting over. Why preserve the story of Husayn? Why tell it? So the human beings could live a virtuous life and form virtuous communities. If that is not the intent, why bother!

In concluding the discussion, one more point needs to be highlighted: The question of the sources of the mytho-theological-historical story. In Sayyid Naqvi’s telling, accounts from past historians such as al-Ṭabarī are intertwined with the ultimate source of Islam’s story: the Qurʾan. We have seen examples of how the Qurʾan is employed again and again to buttress claims about pre-Islamic history, and the word “Islam” is extended to all the previous prophets. Reason sifts through these accounts, probes them, tries to understand them, collaborates in telling them, accounts for contradictions; yet it takes the previous and scriptural tellings seriously. The trust put in the authority of the various versions is related quite directly to the mytho-theological framework itself.((The role of reason in both experiencing, telling, and navigating this story, although significant, remains beyond the scope of this paper.)) That is why to the extent the Qurʾan tells the details, or the plot, it is invoked as the definitive account.

Husayn’s Place within Islam’s Sacred Story

So where is Husayn located in this grand narrative? Since both strands (History of Islam and Husaynology) originate from the same theological vision, History of Islam provides important keys to understand Sayyid Naqvi’s writings on Husaynology. Whereas the particular Shiʿi mytho-theological backdrop was often invoked in his discussion of the various aspects of Husaynology, it largely remained scattered, and was hardly ever presented systematically. History of Islam fills in this lacuna and clarifies the underlying mytho-theological story fully, embracing both the sacred prophetic history and the place of Husayn in it.

From within the sacred story, Husayn can be discovered first right at “the beginning of it all,” and then as a successor to the Ishmaelite lineage with all its glory and burdens. In other words, Husayn appears in two-ways:

- In reference to thirteen lights (see above) right at the origins of all things. In the mytho-theology of Shiʿi Islam, the first light is the Muhammadan light, and the rest of the thirteen lights, of Fatima and the twelve Shiʿi Imams; together the Fourteen Pure Ones. (Husayn is the third Shiʿi Imam.)

- As inheritor of the Ishmaelite lineage, its nobility,((In Shahīd-i Insāniyat [Martyr of Humanity], Sayyid Naqvi enumerates nine unique points that make this family special in their nobility and honor. See pages 36-37.)) duties,((The reader may recall the discussion of these duties earlier in this essay.)) but most crucially, the special role((The roles inherited from Abraham would include: the guardianship of the Sacred House, propagation of the primordial religion of Islam, and readiness to sacrifice all that is necessary in fulfilling the Divine call.)) this lineage has within the Divine script.

Yet that is not all. Within this sacred story, there is a lingering unfinished plot. Recall his comments: “If Ishmael’s sacrifice had been the supreme model of sacrifice before God, it would not have been postponed, nor would it need substitution [of a lamb]. In Divine knowledge, the most perfect and complete sacrifice was yet to come from within Ishmael’s progeny.” As the new Ishmael,((And as carrier of the mantle of his forefathers, he is the also the new Noah, Abraham, Joseph, Jesus, and Muhammad.)) Husayn comes on to the scene to offer the most perfect and complete sacrifice.

There is even more. I have had the occasion to point out Sayyid Naqvi’s critical hermeneutical move of plotting the ethical side-by-side with the historical, and his hierarchic view of the virtues. Recall also his categorical statement about ethical life: “In fact, all commandments, callings, and the entire code of religious conduct rest on demanding sacrifice from humanity, and the sole purpose of appointing prophets, messengers, and religious leaders is to offer its lofty illustrations.” Sacrifice thus becomes the highest ideal of virtuous life. If sacrifice is the highest ideal, then the one enacting “the most perfect and complete sacrifice” becomes the supreme exemplar for a virtue-seeking community. Carrying the mantle of his sacred lineage and covering the expanse of a huge flow of time, this luminous being from among the fourteen lights in “the beginning” appears onto the plains of human history towards its end, and offers the utmost and final example for the most virtuous ideal of sacrifice. He becomes thus the decisive hero of Islam’s sacred story. (The sacred story of Islam of course does not end here. No Shiʿi mytho-theology is complete without the final act of the “Awaited One”, the messianic savior, the Mahdi.)

If sacrifice is the highest ideal, then the one enacting “the most perfect and complete sacrifice” becomes the supreme exemplar for a virtue-seeking community.

In understanding why in Illuminating Islam there could not be a better historical reference than Husayn—the opening quote of this essay—we have had to cover a lot of ground. It is time to forestall a potential misunderstanding. Given the context of modernity and crisis of religion that led to the re-imagining of Islamic tradition on the part of Sayyid Naqvi—a problem most Muslim scholars and thinkers of the last two hundred years have had to grapple with—can Illuminating Islam be construed as “apologetic”, an attempt to defend Islam in the face of criticisms from within and without the tradition?

A gentle “yes”, but a much stronger “no” in response! Unless our author has managed to fool us completely, the mytho-theological underpinnings and its accompanying ethical intent imply that this concern can be gauged through the same interpretive circle. Without delving too deeply into the question—the lack of space prevents that—I refer you to Sayyid Naqvi’s statement regarding why Islam needs to be protected as a religious tradition: “If there is a religion [i.e., Islam], which with respect to its teachings is a supporter of peace and harmony, and of generating a milieu of tranquility and concord, then such a religion deserves to be preserved for renovation (iṣlāḥ) of the world.” (200)((Lā Tufsidū fī al-Arḍ.)) If the thrust of Islam’s mytho-theology is ethical, the thrust of Islam is ethical as well. Since in its encompassing Islam stretches both within space and time (and beyond both as well!), and because it is simultaneously perennial and global, the concern to protect Islam is an ethical concern. In other words, to protect Islam as a religious tradition is to protect the possibility of virtuous life for humanity. In sum, Sayyid Naqvi’s concern for defending Islam is not apologetic; it is again ethical:

The importance given to the event of Karbala is not because these people were related to the Prophet. In fact, it is because the person killed by the sword of Muslims was the true embodiment of Islam. The propagation of this event is also not necessary simply because it was a heartrending calamity that needs to be remembered, but rather to underscore for us the goal for which these calamities were endured. Without doubt, crying for Husayn is perpetual worship and a cause for God’s pleasure. But the real aim of Islam is our practical rectitude. If we have forgotten this aim today—or fail to even consider it—then it is not Islam’s fault. (69-70, emphasis added)((Islām kī Ḥakīmānah Zindagī (Lucknow: Imamiya Mission Hind, n.d.).))

Just as they intersect in narrative, ethical thrust, and message, the mission of Husayn and that of Islam profoundly intersect. Just as Islam is perennial and universal, Husayn as its ultimate hero is too. That is why Sayyid Naqvi prescribes, not just to Muslims but even non-Muslims who were familiar with the Karbala episode, to reflect on that episode and derive moral and social implications from it. In Ḥusayn kā Payghām ʿĀlam-i Insāniyyat kay Nām [Ḥusayn’s Message to Global Humanity] Sayyid Naqvi invokes the voice of Imam Husayn speaking to his non-Muslim audience as follows:

You who celebrate my commemoration and revive my remembrance: its outcome should also be that you are aware of my goal. Strive to follow this [goal] in your practice. Remember! I do not belong to any particular group. Only the one who reflects on my principles and perspective, and learns its lessons could benefit from me. (24)

Seen from the mytho-theological lens and the hermeneutical circle it becomes clear that while the universality of Husayn’s message can serve numerous other purposes, for example, demonstrating the truth of Islam to the modern world, these concerns could only be peripheral. But a more significant task faced Muslims: “the real struggle for rectification (iṣlāḥ) will be the spreading (tarwīj) of the teachings of the [Islamic] religion and the attempt to turn people into its adherents.”((Lā Tufsidū fī al-Arḍ, 201.)) In the task of spreading “the ethical vision of Islam” and winning more adherents, Sayyid Naqvi finds Husayn, and his heroic act at Karbala the best resource. Humanity needed to be invited to Islam through introduction to its ultimate hero. Notice the title and opening passage from the treatise Husayn’s Message to Global Humanity((Ḥusayn kā Payghām-i ʿĀlam-i Insāniyyat kay Nām (Lucknow: Sarfarāz Qawmī Press, 1959).)):

Listen carefully! The voice of the innocent martyr of Karbala is reverberating in the air. “O those who dwell in my Lord’s spacious earth…I do not call upon you by your sectarian and communal names. Your opposition dissolves because of your sympathy for my immense humanity and your lamenting my being greatly oppressed, just as rivers and cascades lose their anxiety and restlessness in the serene ocean. I invite you all to come and learn who I was and why I stood up. (3)((Also see “Ḥusayn awr Islām” in Nigārshāt-i Sayyid al-ʿUlamāʾ (Lahore: Imamiya Mission Pakistan Trust, 1997), another text which introduces Husayn’s life and mission at Karbala in a similar fashion. See pp. 153-180.))

An interesting short treatise in this regard is “What does Commemorating Husayn Demand from Free India?”((“Ḥusayn kī Yād kā Āzād Hindūstān say Muṭālbah,” (Lucknow: Sarfaraz Qawmi Press, 1950).)) He critiques the post-Christian Western obsession with materialist power, an obsession which was a consequence of the underlying materialistic worldview (mādda parastī) that had come to dominate Western thought and culture. In his view, this materialistic worldview had led Western writers to study Islam’s political history from the point of view of only those who appear to be “the conquerors”, regardless of the ethical-spiritual criteria of these conquests. That is why, says Sayyid Naqvi, the Karbala episode has altogether been ignored by such writers and thinkers. He contrasts this view with Eastern or Indian spirituality which sees warfare from a spiritual point of view, and therefore has always appreciated the endeavor of Husayn as witnessed in the writings and sayings of major Indian leaders and intellectuals such as Gandhi and Nehru, among others. In conclusion, Sayyid Naqvi notes that:

This proclamation needs to be brought into the limelight in “secular” (ghayr madhhabī) India, for even when being “secular”, the people of India cannot step out of their [particular] sect and regional community (qawm). This sacrifice [of Husayn] is guidance for every sect and regional community. That is why the commemoration of the sacrifice of Husayn ibn ʿAli can make claims on free India akin to those made by every sect and regional community. (10)

The supreme martyr-hero of Islam had transitioned into becoming the martyr par excellence of humanity.

By the time Sayyid Naqvi puts together his magnum opus Shahid-i Insānīyat [Martyr of Humanity] on Husayn, the supreme martyr-hero of Islam had transitioned into becoming the martyr par excellence of humanity—the title of Sayyid Naqvi’s definitive biography of Husayn. The mytho-theological story of Islam and Husayn with its full thrust toward the ethical was now re-imagined in a global modern context, and an exceptional figure of human history was universalized to become the martyr par excellence of global humanity:

Although from the point of view of its occurrence, every event of the world is related to a particular land, a particular community, and a particular class (ṭabaqah)—[and] from this angle the incident of Karbala is also [related to the] land of Iraq, country of Arabs, family of Hāshim, and the community of Muslims—but events gain universality and depth through attributes and outcomes that relate to the whole of humanity [transcending] the distinctions of religion, race, or nation. If seen from this point of view, the incident of Karbala from multiple viewpoints is the focal point of the whole of humanity. (26) First, hatred of the oppressor and sympathy for the oppressed is part of human nature…Although numerous prophets and [God’s] friends suffered oppression in the hands of worldly people—indeed, many innocent people were killed or imprisoned, and (their property) plundered—but overall, those hardships that each of them had to face individually were combined in the personality of Imam Ḥusayn (peace be upon him). That they gathered in him simultaneously [means that] the oppression he suffered was unique in its example.

Second, his oppression was not the oppression of someone who was helpless; it is not, for example, like someone who is attacked by a robber, robbed of everything, and then murdered. This person is also oppressed (maẓlūm) and would also draw sympathy. But this oppression is not volitional. There is also no act associated with it that is praiseworthy from the moral point of view. Imam Husayn’s oppression is not of this kind. He bore all these adversities to support a righteous cause and in preservation of a principled stance. This is sacrifice.

Third, his sacrifice did not have an aim that was contestable from the point of view of other religions. Human morality and attributes have a station upon which all religions come to agree. The true foundation of all religions—upon which they have been erected—is to raise human morality to its [highest] limits. It is a different matter for the temporal differences [among these religions] to lead to some variations in certain injunctions, or for the principles of some religions to be increased or reduced due to later generations’ misunderstandings. But the real axis [of all religions] is morality and the perfection of humanity. The aim of Imam Husayn was this shared point of view…

Fourth, examples of diverse ethical and [human] attributes presented by Imam Husayn and his companions at Karbala are such that all members of humanity can benefit from those examples. This is the reason why despite mutual differences and emotional struggle the world has come to a consensus (yagāngī) about Karbala: nations of the world have all equally accepted its importance. Even after the passing of hundreds of years of this important incident, their interest in it has stayed, and has at times grown. (26-8)((Shahīd-i Insānīyat.))

…[B]ut events gain universality and depth through attributes and outcomes that relate to the whole of humanity [transcending] the distinctions of religion, race, or nation.

Sayyid Naqvi is convinced that the one who appears on the pages of history seemingly leading a political revolution against a mighty ruler is in fact driving a revolution of an entirely different order. He wants the human community of the world to recognize that unlike other revolutions, Husayn did not seek the destruction of an empire; instead his sacrifice was for the cause of sculpting the moral and intellectual consciousness of humanity:

The goal of Imam Husayn—as discussed in this book on various occasion—was not to destroy Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiyah’s government in direct material ways. If this is what he had intended, he should have employed material ways, and would have gathered military power around him. Instead, he struggled for [the sake of] a true intellectual revolution. Obviously, military power and the sword can cut human bodies to pieces, but it cannot change the mindset of people. Therefore, he did not pay any attention to that: His sole objective was to change the mindset.

The true and eternal benefit of the incident of Karbala is quite different from the reactionary, material revolutions and vengeful results that occurred during that period. Rather, they are related to that moral force which is the true guarantor of the right restoration and guidance of humankind’s mentality. (536)((Shahīd-i Insānīyat.))

When recognized from within Islam’s sacred story, Imam Husayn carries the noblest prophetic lineage and ancestral duties that come with it. He is the new Ishmael who has come to offer, willingly and with patience and gratitude, the most complete and perfect sacrifice. Above all, he is a light among the fourteen primordial lights that came to not only illuminate Islam, but also to illuminate through Islam’s rays the ethical and moral norms for all of humanity. And that is precisely why he needs to be shared with the global human community, not just as hero of Islam, but that of humanity.

To restrict the personality of Imam Husayn and his immortal feat (kārnāmah-i jāwīd)—with all the graces and blessings [that pour from it]—to a single group is against the spirit of Islam, [the spirit] that underlies calling the Creator of the universe “Lord of the worlds” (rabb al-ʿālamīn). When the lordship of God cannot be restricted to any particular group, then restricting the sacrifice of a martyr like Husayn to a single group is also completely wrong. In fact, the benefit of his martyrdom concerns all those people who desire to draw from him some lesson about human life. (539)((Shahīd-i Insānīyat.))

In view of our discussion it is hardly surprising then why Sayyid Naqvi would claim that in “illuminating Islam” he could not find a historical figure more fitting and compelling than Husayn. That is why, fully aware of this indebtedness to Husayn and his heroic deeds, he was never tired of praising him:

O Husayn b. ʿAlī! My greetings to you. Till the last moment you did not let go of your sense of duty or of calmness and patience. You sacrificed your life, dignity, everything. You did not deem anything more worthy than your grandfather’s sharīʿah. You made the world remember the lesson of true tawḥīd. You died temporarily, but gave new life to Islam. Every drop of your blood that touched the ground of Karbala breathed new spirit into the sharīʿah. Religion owes you its life, and Islam can never repay you for your beneficence (iḥsān)((Literally, “raise its head in the face of your beneficence.”)) toward it. On our behalf, may God present you with the gift of blessings. (317)((“Banī Umayyah kī ʿAdāwat-i Islām kī Aik Mukhtaṣar Tārīkh awr Maydān-i Karbalā kā ʿAzīm Kārnāmah” in Nigārshāt-i Sayyid al-ʿUlāmaʾ, pp. 304-317.))

Syed Rizwan Zamir is an associate professor of Religious Studies at the department of religion at Davidson College in Davidson, NC, where he teaches introductory and advanced courses in the area of Islamic studies, specializing in Islamic thought and spirituality. Dr. Zamir’s Ph.D. dissertation was on the religio-intellectual thought of Sayyid ʿAlī Naqvī and his profound influence on the religious and social landscape of the Shiʿi community in South Asia. He received a B.A. from the University of Punjab and also James Madison University. Dr. Zamir earned his Ph.D. from the University of Virginia.

ً

ً